Beliefs and emotions

I recently read a comic from The Oatmeal (Matthew Inman) that has really stirred me, in a good way. So first, go ahead and click the image below to go to the comic. I promise, it’s super good!

I really liked this comic because it does an excellent job at progressively teaching three lessons that trace my own personal development and understanding of emotions in the last few years. These are:

- Facts are important but emotions get in the way of facts

- Emotions are deeply instinctual and you can’t eliminate them

- Given that you can’t avoid getting emotional, the next best thing is self-awareness

Facts are important but emotions get in the way of facts

We all have beliefs that matter to us. Beliefs that we react more strongly to when challenged. Sometimes it’s because we have a stake in it, sometimes it’s because it feels like an attack on our identity, sometimes it’s because we’ve believed something to be true for so long that we feel stupid to be wrong.

In his comic, Matthew Inman calls it the backfire effect.

What the study revealed was that the same part of the brain that responds to a PHYSICAL threat responds to an INTELLECTUAL one.

There are other similar phenomena in psychology. If you are not familiar with this terms, you can read up on confirmation bias, group polarization and belief perseverance. Those are just a few examples.

This subject has been getting a lot of discussion lately. Think about how in today’s political climate, many people seem to hold their feelings to be just as valid as facts.

Quiz: what came to your mind as an example of feeling-driven people? Was it Trump supporters reading Breitbart? Liberal college students censoring opposing views? Did reading this question spike your emotional barometer? What does that tell you about your own beliefs? This isn’t a question of left v.s. right, everyone is driven by feelings.

I can’t emphasize enough how important of a lesson this is. However, my social circle consists disproportionately of college educated students in technical (scientific, mathematics and engineering) fields. While it’s difficult to put facts ahead of emotions no matter who you are, most people I know have thought about this at some point and value logic to some extent, sometimes quite strongly.

Where it gets interesting is the next two lessons.

Emotions are deeply instinctual and you can’t eliminate them

The comic continues with the following:

This area of the brain is known as the amygdala and is the emotional core of your brain. Unfortunately, it makes us biologically wired to react to threatening information the same way we’d react to being attacked by a predator.

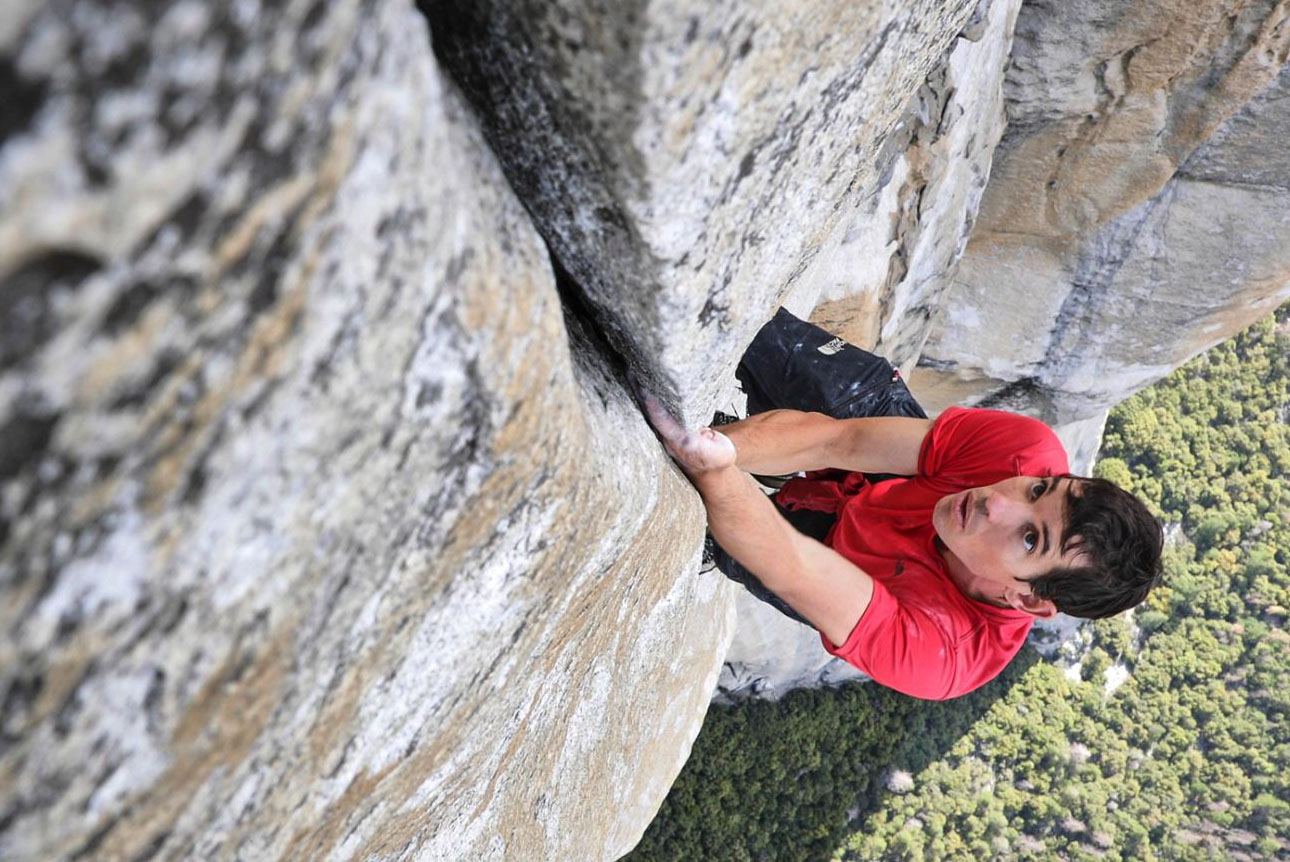

Now, it is possible to train ourselves to stay calm in the face of intellectual threats in the same way we can train ourselves to stay calm in the face of physical threats. As a simple example, people who grew up with large dogs will probably be less afraid of large dogs thanks to large amounts of exposure and experience dealing with them. Similarly, it’s possible to stay more calm in the face of intellectual threats if you learn that some things (like admitting you are wrong) are less scary and less likely to cause harm than they sound. And some people are naturally born more calm than others. An extreme example such as Alex Honnold doesn’t feel fear like we do - his amygdala shows far less response to threatening images!

Alex Honnold free-soloing El Capitain

Yet, training will only get us so far. There will always be new situations that we haven’t encountered that will put us on guard. And often time, we think we become more rational, but we haven’t eliminated our emotions. We just shaped how we express it. Some expressions are perceived in society as less emotional than others. A raging outburst is seen as more emotional than a passive-aggressive comment which is seen as more emotional than keeping a blank face. But the emotion might still be boiling underneath 1.

This is crucial because I’ve noticed that many technical people, myself included, have learned to disguise our emotions using its opposite: arguments that have traits of rationality. We take vocabulary from science and logic (e.g. “X does not imply Y”). We quote psychological and statistical biases. However, I say that the arguments have traits of rationality, because being truly rational is extremely difficult. Humans can’t be perfectly rational, so we use heuristics. Even in perfect-information games like Chess or Go, we learn that certain formations are more advantageous, which then trips us up against superior opponents like AlphaGo 2.

Thereing lies a danger of being smart, but not smart enough. Humans are not rational creatures, they are rationalizing creatures. People who’ve studied ways of being rational (directly or indirectly through exposure to technical fields) gain a lot of tools to rationalize, without really being rational. As using those tools often gives us satisfaction, they’re easy to overuse.

Here are some forms that I’ve seen emotional rationalization take:

- Selectively exploiting the uncertainty in the world.

- Formal mathematical proofs are rarely achievable in the real world. Instead, only partial pieces of evidences are available to weight in support or against an argument. This makes it easy to dismiss evidence when convenient. First, the evidence is not good enough because it’s just an anecdote. Then, the data is various degrees of imperfect: the person gathering it has an agenda, it doesn’t prove causation, etc. These are legitimate objections, but since they can almost always be used, it’s easy to use them only when we emotionally object to a piece of evidence.

- Key: absence of evidence does not imply evidence of absence.

- Cargo-culting psychology (e.g. confirmation, sampling and survivorship bias). When an idea or fact is presented by a human, there’s always the possibility that the presenter willingly or unwillingly ignored counterclaims. Again, it makes it easy to dismiss evidence using those arguments more often when our emotional barometer is high.

- Key: even if those biases are indeed present, do they completely invalidate an argument?

- Formal mathematical proofs are rarely achievable in the real world. Instead, only partial pieces of evidences are available to weight in support or against an argument. This makes it easy to dismiss evidence when convenient. First, the evidence is not good enough because it’s just an anecdote. Then, the data is various degrees of imperfect: the person gathering it has an agenda, it doesn’t prove causation, etc. These are legitimate objections, but since they can almost always be used, it’s easy to use them only when we emotionally object to a piece of evidence.

- Overweighing the pros and ignoring the cons (or vice-versa)

- Most solutions to human problems (e.g. candidate interviewing) are imperfect and involve tradeoffs with lots of pros and cons. Everybody has the tendency to overweigh one or the other depending on our preconceptions, but it’s especially easy for well-educated people to generate a lot of pros or a lot of cons.

- Key: under emotion, am I weighting all aspects of the debate fairly?

- Most solutions to human problems (e.g. candidate interviewing) are imperfect and involve tradeoffs with lots of pros and cons. Everybody has the tendency to overweigh one or the other depending on our preconceptions, but it’s especially easy for well-educated people to generate a lot of pros or a lot of cons.

- Selectively “seeing ahead” (a specific form of the previous example).

- People who read a lot about history know that history is full of unintended consequences, which is easy to abuse. For example, one might argue that the invention of the atomic bomb has deterred enough wars that its death toll has been “paid off”, or that food aid to developing countries is overall harmful since it drops food prices and prevents sustainable local farming. This could be correct. However, being knowledgeable makes it easy to generate a lot of possible unintended consequences.

- Key: under emotion, do all the consequences favor one side of the argument?

- People who read a lot about history know that history is full of unintended consequences, which is easy to abuse. For example, one might argue that the invention of the atomic bomb has deterred enough wars that its death toll has been “paid off”, or that food aid to developing countries is overall harmful since it drops food prices and prevents sustainable local farming. This could be correct. However, being knowledgeable makes it easy to generate a lot of possible unintended consequences.

- Nitpicking

- Humans are imperfect communicators. It’s easy to make minor mistakes in expressing our ideas. A form of emotional rationalization is to nitpick on the small details either to believe that the other person is wrong, or to derail the discussion entirely to prevent them from finishing their point. Being smart enough to pick up those details can actually get in the way of seeing the big picture.

- Key: am I refuting the central point and could I be using a steel man argument?

- Humans are imperfect communicators. It’s easy to make minor mistakes in expressing our ideas. A form of emotional rationalization is to nitpick on the small details either to believe that the other person is wrong, or to derail the discussion entirely to prevent them from finishing their point. Being smart enough to pick up those details can actually get in the way of seeing the big picture.

Given that you can’t avoid getting emotional, the next best thing is self-awareness

So what can you do if emotions are going to happen anyway?

I sometimes pretend the amygdala of my brain is in my pinky toe. When a core belief is challenged, I imagine it yelling insane things to me. I let it yell. I let it have its moment. I let the emotional cortex fight its little fight. And then I listen. And then I change.

The first step is to accept that emotions are a totally a human thing to have and there’s nothing to be ashamed of. Within certain circles of intellectuals, emotions are typically looked upon negatively. This might be for good reason, and due to negative things we’ve seen people do as a result of emotions. But then, social pressure causes people to deny that it’s there to maintain their social image. All the while, the emotion is totally having its effects.

Here’s the approach I try to take. First, I try to recognize when it happens, what effects it has on you, and what forms it takes.

I try to recognize it quickly. I find that it is possible to catch myself rationalizing. In that case, I try to take a step back. I try to cut my line of thought right there or start winding it down. I can get back to it later, or try to continue the conversation in a more collaborative tone. For example, I can ask the other person to explain their point of view more and just listen. For me, talking is more stressful than listening.

That’s ideal, but it’s hard to do. I can’t always do it as much or as quickly as I’d like. Fortunately, I believe the most important thing is not to dissipate the emotion as quickly possible but rather, to not let emotions get in the way of long-term improvement.

The obstacle here is belief perseverance. Whatever people say they believe when the emotional cortex is having its little fight, there’s a strong chance that they stick with it due to saying it. Old information can get in the way of absorbing new information, including the information that you generate yourself.

However, if I can accept that my amygdala is firing excitingly, I find it easier to correct things I said in a calmer state of mind. Otherwise, if I deny it, I’m likely to stick with warped beliefs for quite a while, because humans just like to be consistent.

And this whole process is an important one to learn because rarely are people willing to tell you you’re being emotional. It’s not always obvious when someone is emotional and when unsure, we prefer not to assume. When it is obvious, saying it makes things worse. Other people are just as likely as you to be tricked by emotions disguised under the trait of rationality.

So the only person that can figure all this out is yourself. So as The Oatmeal says:

I’m not here to take control of the wheel.

Or to tell you what to believe.

I’m just here to tell you that it’s ok to stop.

To listen.

To change.

Thanks to Anna Harrington, Hang Lu Su, Logan Buckley, Shirley Du for reading over and reviewing this blog post!

-

This depends of course on your definition of “emotion”. I like to consider the physical aspects of emotion (temperature rising, body tension, chemicals released in the brain) that are related, but not the same as the expression of the emotion. ↩

-

AlphaGo made many moves that Go experts would have previously said to be bad practice, like playing on the 3-3 point, and won. Go experts subsequently started adopting those moves. Experts now consider AlphaGo to be definitely superior to humans. ↩