Guide to conducting mock interviews on campus

In the previous blog post, I explained why you should consider offering mock interviews for other students to help them learn interview and algorithm skills. Now, assuming you’re interested, I will guide you on how to do it effectively, all the way from logistics to creating a good experience for the interviewee. This blog post is a bit more of a manual/reference guide, but the TL;DR is:

- Start small, let yourself get used to offering mock interviews

- Be encouraging and go with your intent not just to teach technical skills, but help them get less nervous about interviewing

- Pick good interview questions that teach concepts, avoid single-insight get-it-or-you-don’t type qusetions

- Take the time to give good feedback

- Ask for feedback about the mock interview and keep a journal of how things went

Logistics

Starting out

To conduct mock interviews, you first need volunteer interviewers.

If this is your first time, you can just start with a friend or two, or even do it by yourself. The logistics of signing up for the mock sessions can be as simple as making a post on one of your university’s Facebook groups and following up with whoever responds in the comments. There’s no need to make it a Big and Official Thing right away. In fact, it’s better to just start feeling it out and seeing how you like it.

When Shine first started offering mock sessions, Alice and I just jumped in. Then we kept doing it, and gradually other people we knew started volunteering too. But we weren’t initially planning on making it an ongoing thing. It was a one-off try-for-fun event.

Signups

The easiest way to manage signups and track interviewee status is a combination of Google Forms + Google Sheets.

You could go out and build your own website with signups, being in tech and all. But it’s worth asking yourself if you’re at the stage where it’s worth the effort. If you’ve got someone in your team who’s really good at cranking out web apps quickly and can do it in a day or two, sure. Otherwise, unless you’re already into the hundreds of signups, it’s easiest just to use existing solutions and good old manual tracking.

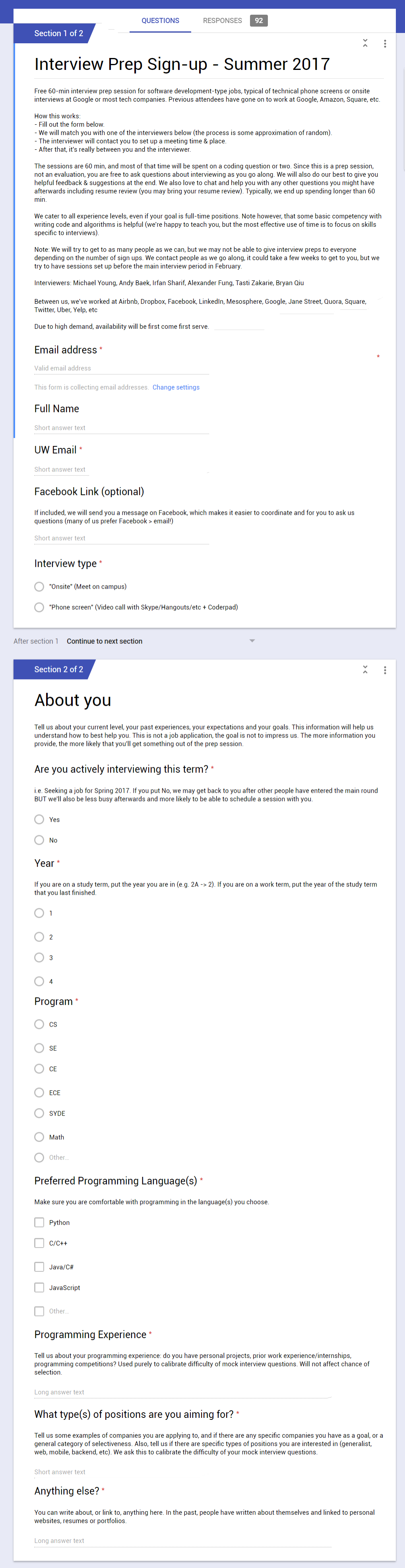

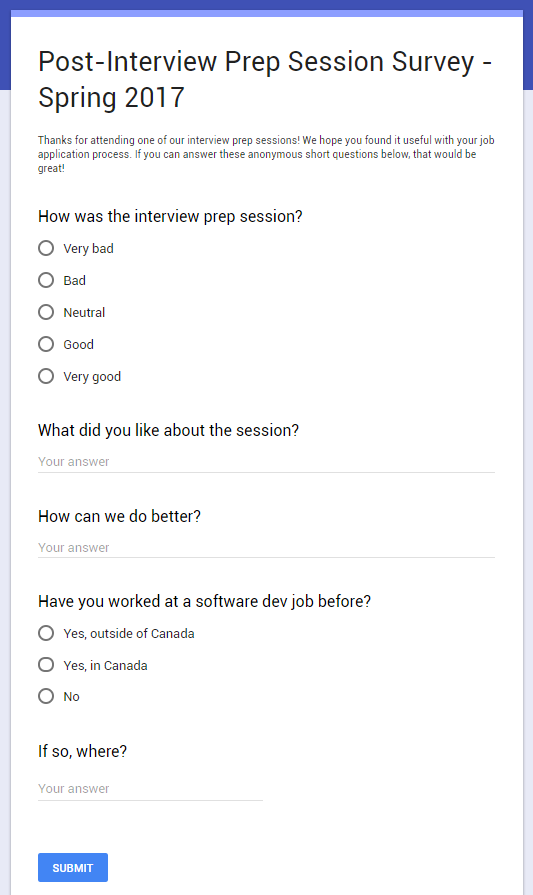

For reference, our Google Forms signup sheets looks like this (click to expand):

You can copy our template verbatim, but I recommend customizing it as appropriate for your situation. Make sure you include the following information and ask the following questions.

- Will you offer only technical interviews? Or will you offer non-technical interview practice too (e.g. behavioral questions)? Make sure that you clearly indicate what kind of mock interviews you offer, so that the interviewee doesn’t come in with the wrong expectations.

- What timeline are you looking at? When can they expect to be contacted?

- Ask for their contact information, obviously.

- If you think you might have interviewers and/or interviewees that will not be physically on campus (e.g. doing an internship in another city), add the option of having a Skype interview.

- You can ask for some personal information, both for statistics purposes and to calibrate your interviews. This includes their year, their program, their past experience, etc.

- What programming language do they want to use? If not all of your interviewers are comfortable with doing an interview in most popular languages, this helps pair them with the right interviewers.

- From my experience you don’t really need to worry about obscure languages, almost everyone uses Python or a C-language (Java/Javascript/C++).

- What are the interviewee’s goals? Some people just want their first interview experience, others are aiming to get into the most selective companies.

- Additional information. Since you’re likely to get more signups than you have capacity for, you may need to select who you give mock interviews to. Which means information like their resume/websites is helpful.

Important note: the point is not to give mock interviews only to the strongest students, they’re not the ones who need it the most. On the other hand, it tends to be more fun and satisfying to help students that are more motivated v.s. “I just want a job for money”. It’s up to you to figure out what criteria you want to use.

Advertising

You can post the signup sheet on Facebook groups, /r/<youruniversitysubreddit>, or anywhere else appropriate. Most of the signups will come in the first few days and you might want to keep an eye on the number of signups and close the form when you reach capacity (alternatively, look online for an automatic way to do that).

Signup tracking

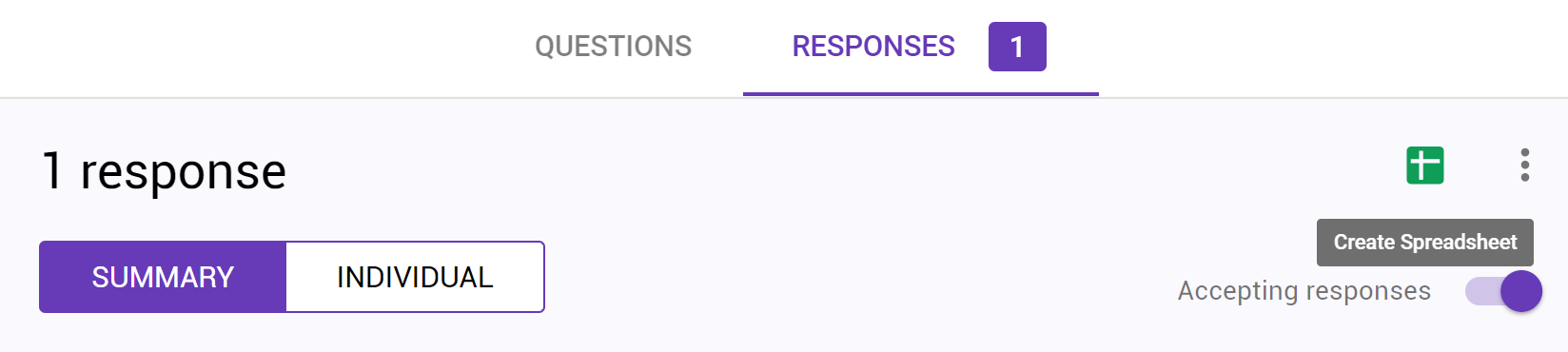

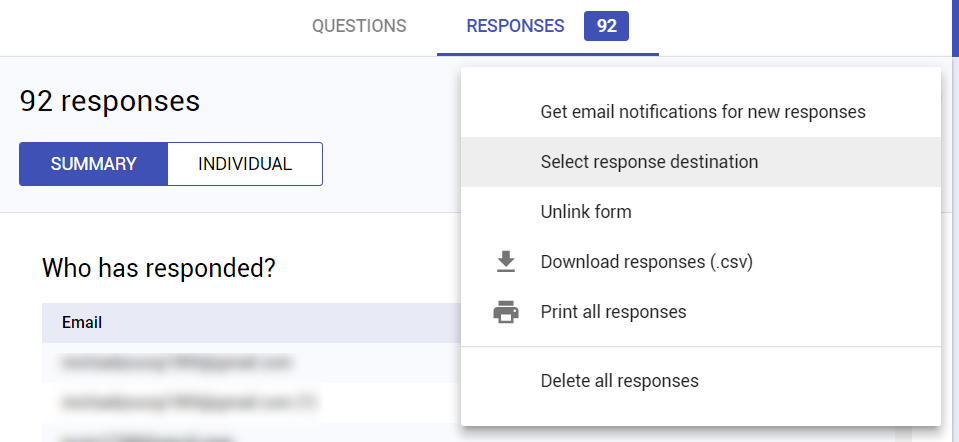

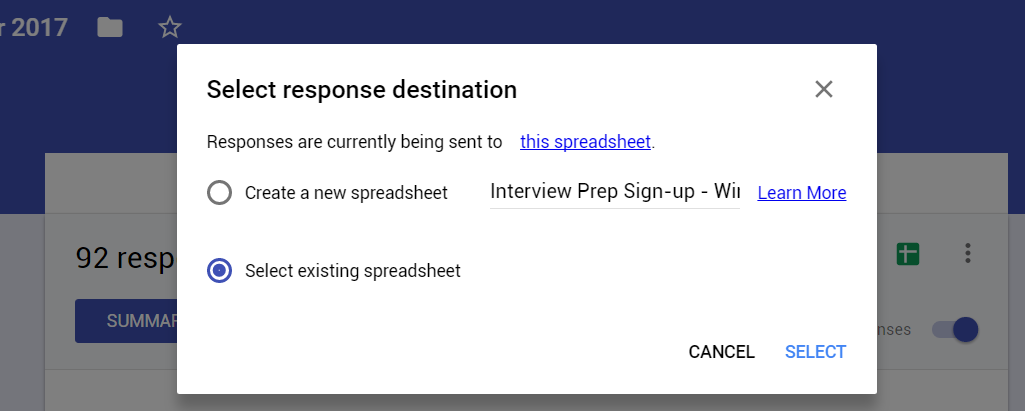

The nice thing about Google Forms/Google Sheets integration is that you can setup the survey responses to automatically show up in a Google Sheets document. There, you can add new columns for interview status and assigned interviewer. To do so, create a new spreadsheet from the responses section:

You can also use “select destination” from the dropdown menu.

Here is how it looks like on our end:

The statuses we use are [blank], Contacted, Scheduled, Completed, No Reply, Flopped (didn’t show up), Cancelled. You can automatically assign color to different statuses by going in Format > Conditional Formatting… > Add New Rule + > Text contains.

The most convenient way to organize this sheet is to sort by Interviewer, then Status. You can do this by doing in Data > Sort Range…, selecting the Interviewer column and then clicking on “Add another sort column” to select the Status column.

Assigning interviewers

You can assign interviewers to interviewees however you want. There will be some constraints such as programming languages. However, since most people use a C-like language or Python, I haven’t found this to be a difficult constraint to satisfy.

Perhaps the more important thing to keep in mind is to be “fair” in how the study years are “distributed” among interviewers. When interviewing freshmen, you generally have to pick easier questions and a lot of the time ends up spent on teaching basic coding concepts or tricks (unless they have a lot of prior experience). When interviewing older students, typically juniors who are trying to get into top companies (e.g. Big 4), you get more freedom to try out difficult and fun questions. Ideally, all the interviewers get a mix of both.

Conversely, you or some of your friends might not feel comfortable giving mock interviews at the level aimed at helping people get into selective companies. That’s totally fine, you don’t need to. You can just focus on preparing people for their first internships. There’s probably going to be a long line of people who’d like that anyway!

If there’s just 2-3 of you, you can use some simple assignment scheme like “you take the odd numbers and I take the even numbers”. If there’s more, you might want to order interviewees by their year of study first and then distribute. Feel free to write a script to do that if it sounds fun to you since you’re a programmer, but it might be faster to just do it by hand.

Whatever method you use, you might want to allow your volunteer interviewers to “swap” candidates for a variety of reasons. That can include “I know this person already”, “you should interview this web developer instead of me because you have more web experience”, etc.

Before the interview

Contacting the interviewee

At this point, we let the interviewer handle contacting the interviewees and arranging a meeting time and place. You can use the templates below, or write your own.

Hi <person name>! I’m <your name>, I’m in <year> <program> and I’m helping <person who advertised the signups> with the interview practice sessions. I’ve interned at <company name> in the past. Did you have a preference for online interviews (e.g. skype + shared text editor) or whiteboard interviews? I’m on campus next term so I can do either.

(The first time I did the interview prep sessions, I joined in after Shine had advertised signups, so I needed to provide that extra bit of information.)

Hi <person name>, I’m <your name>, one of the people conducting the interview prep sessions. Thanks for signing up. When would you like to do one? I’m available as soon as next week, but it’s also fine if you want some time to prepare. Finding a spot on campus

If you conduct an in-person (whiteboard) mock interview, you’ll need to scout around for a spot on campus with a whiteboard. Ideally, it would be located near a well-known spot on campus that you can meet them at. Then, you can head to the whiteboard. This is better than having them find you in a random corridor of some random building.

Don’t forget to communicate to them how to identify you.

Equipment

Whiteboards often won’t have an eraser or markers that work. Make sure to bring your own. For markers, I recommend buying thin-tipped ones, as they are much more readable from a close distance. Thick markers are meant for lectures, where people could be sitting very far.

Don’t be surprised if your marker runs out after just a few interviews. One of my professors said that a marker only lasts him for a lecture. Granted, he was the type to write everything on the board, but still.

If you do Skype interviews, use a service made for writing code rather than Google Docs. Options include Codeshare.io, Kobra.io and CodeBunk.

Preparing a question

Before contacting candidates, all interviewers should prepare some interview questions that they would feel comfortable asking. Ideally, your questions should cover a range of difficulty levels to match the range of experience levels students have. It’s also nice if you have questions that are good exercises for a particular topic (e.g. graphs, dynamic programming). Recursion questions are a common request from my experience.

Question difficulty

Easy questions, suited for freshman, will generally involve some simple application of basic control flow constructs. For example, one question that I like is “print the contents of a 2D array of strings in such a way that the columns are aligned”. It requires the interviewee to solve the question in two steps, the first being to calculate the maximum length of each column.

If I want to challenge someone without making any assumptions about their algorithms or data structures knowledge, I like to ask “parse a CSV file” which only requires very basic for-loops and if-statements to solve, but has a non-trivial edge case.

Medium-difficulty questions start to make use of dictionaries, stack/queues, recursion.

Hard interview questions will often make use of a combination of multiple data structures or have some tricky edge cases to solve.

Finding questions to ask

I strongly recommend asking questions that you are familiar with, rather than looking for interview questions online. Those are often going to be problems that you’ve been asked during one of your own interviews. It’s also possible to make interview questions out of real problems you’ve encountered at work or in your side-projects. Interviewees tend to like “realistic” questions.

For example, I had to write a procedure that would highlight the words from a search query inside the search results, for a friend’s website. It turns out that there are edge cases which make this non-trivial.

In the question, I would give the following example. Say the user types the search query “water” and one of the results is “water at university of waterloo”. Then add bold tags to all instances of the substring “water”, to get “water at university of waterloo”. By itself, the question can be a little bit difficult because interviewees sometimes have difficult keeping track of insertion indices when the substring shows up more than once. If time permits, the full version of this question also require that they handle the case of overlapping words in the query. Believe it or not, I found that the full version is one of my hardest questions.

If you really need to look online for interview questions: try to not only solve them, but to solve them in more than one way. While the job of the interviewee is to find a path to the solution, your job as the interviewer is to know all paths to the solution and guide the interviewee through them.

Good interview questions

- Avoid “you get it or you don’t” type of questions. That is, avoid questions that are all about finding a particular trick or insight. Prefer questions that can be worked through progressively and require the interviewee to write more than just a few lines of clever code.

- Remark: dynamic programming questions tend to be “you get it or you don’t”.

- Split longer questions into separate stages. Sometimes, this means ignoring some edge cases in the problem, such as large inputs. You don’t want to overload the interviewee with too many things to think about at once, that’s stressful.

- Questions set in realistic situations, especially if they’re inspired by problems you’ve faced and solved are great. They’re well-appreciated by interviewees. Real-life problems make the whole process seem much less arbitrary.

During the interview

The role of the interviewer

It’s important to remember your role conducting mock interviews, and the circumstances of the people you are interviewing. You’re looking to help students succeed in their future interviews.

You’ll be doing some of that by training the person on technical aspects, challenging them with new problems and giving them problem solving or communication tips. But in a lot of cases, the major ways you’ll help them is by helping them get over nervousness and uncertainty, calibrating them properly and getting them to take action and improve where needed. Different people have different needs, as can be seen in the diagram below.

| Candidate is | Confident | Not confident |

|---|---|---|

| Competent | A few pointers and they’re ready to fly! | Give encouragement and help getting over nervousness and they can perform at full potential |

| Not competent | Being harsh might be necessary. If they’re overconfident, they won’t improve! | They have a long way to go! Show them a realistic path to improvement. |

On the topic of confidence. Many of the people who you’ll be interviewing will have minimal technical interview experience, or no interview experience at all. What they need is to get comfortable with the process of interviewing and focus. Even if they’re able to solve problems, there’s a lot of other things that will be going on during the interview that will distract them. Am I allowed to use this helper function? Am I talking too much? Too little? Is my solution right? Do I have to get it perfect? AhhHhhhHhhhhh.

For this reason, it’s important that you walk in the interview with an encouraging attitude, with all your intent on making the person feel comfortable. Now, I think all interviewers at all companies should do that, but it’s especially important when giving mock interviews. Working at the emotional level is important. You want to convince them that interviewing is a very learnable skill, that they can “do it” if they keep practicing. You want them to be able to walk into their next, real interview confident.

Being encouraging doesn’t mean you have to lie about how well they’re doing of course. It’s about encouraging to get better. Especially for students that are overconfident, it may be necessary to deflate their ego a little (as it’ll happen eventually anyway). But again, keep in mind that the goal is to get them to be realistic and keep improving. Not to discourage them.

The thing is, confidence also helps people take action to practice. It may seem obvious that if you’re behind on technical skills, you need to catch-up by practicing. But it’s quite common for people to be aversive to practicing because they’re struggling and it makes them feel bad.

I know that for some interviewers, it won’t feel very satisfying if your primary contribution turns out to be as the cheerleader. If you have a lot of experience with algorithms and interviews, it’s probably the thing you most want to share. The key is to keep in mind is that you have credibility in this area, so whatever you say has more impact (than a random friend) and they’re more likely to take it to heart. Power combined with warmth is especially effective.

Do

- Repeat that this is not an evaluation and that you’re there to help. More than once.

- Give small feedback of how well they’re doing periodically.

- Encourage them to let out their thought process by asking “what are you thinking about?”.

- Explain the interviewing process as you go along (if they ask “can I use this library function”, it’s an opportunity to explain how it’s fine or not to use them in interviews).

- Concede that your problem is hard if you chose to give them a hard problem.

- Be patient in giving them time to think.

- Keep a list of suggestions as you go along and give it to them after the interview.

- Ask if they want a hint.

- One good way to give a hint is to ask a question about a potential edge case that leads them to focus on the right part of the problem.

- Otherwise, it’s preferable to ask if they want the hint before giving it directly.

Don’t

- Get picky about syntax error and library function names during the interview unless they represent a fundamental misunderstanding of the language they’re using (otherwise it might still be worth pointing them out afterwards).

- Interrupt them on little implementation details or errors as soon as they show up (this includes off-by-one errors, writing something more verbose than necessary, misnamed variables). There’s natural pause points where you can point those out (e.g. after they’ve implemented one function or when they’re done).

- Throw complications at the problem without stating that what they’ve done is good so far and that you’re moving on to the next stage of the problem (otherwise they feel dumb for not having considered it).

- Feign surprise.

“You shouldn’t act surprised when people say they don’t know something. This applies to both technical things (“What?! I can’t believe you don’t know what the stack is!”) and non-technical things (“You don’t know who RMS is?!”). Feigning surprise has absolutely no social or educational benefit: When people feign surprise, it’s usually to make them feel better about themselves and others feel worse. And even when that’s not the intention, it’s almost always the effect.” - Recurse Center User Manual

I wrote this list as an idealistic view of what I try to strive towards. But even as the one who wrote it, I notice that I don’t always succeed in following my own rules. That’s fine, being a practice interviewer takes practice just like interviewing does! You will sometimes make mistakes or get impatient, and it does not mean you’re a bad person. The important thing is to improve in the long run.

Giving feedback

This part is important, what you say can make a lot of difference!

What feedback you decide to give is obviously very circumstantial, but here are some tips that may help give good feedback:

- At the risk of sounding old, start with the positive feedback, and give a good balance of both positive and negative as much as possible. People need to know what to fix, but they also need to know what they did well so that they can keep doing that.

- Give feedback that helps the candidate achieve their goals. Feedback for inexperienced student can be focused more on a few general but high value tips, and useful things they could learn next. Feedback for experienced students who aim to get into top companies is aimed at helping them perfect their interview skills and involve more nitpicks and higher expectations.

- Focus on important feedback that is useful outside of the mock interview. That means that things like off-by-one-errors, mismatched parentheses, etc are less important than tips about having structured approach to problem solving, for instance.

- Make sure to leave enough time so that you’re not in a rush when giving feedback. You want the interviewee to be relaxed when receiving feedback, so you’ll need to be too.

After the interview

At this point, you’ve done your job and you can walk home happy that you did something positive for someone’s life. And you don’t have to do more than that.

However, you can get more out of the experience for yourself by going the extra mile and doing a bit of bookkeeping.

Feedback forms

We have an anonymous feedback form that our interviewers send after the interview. This helps us know what we did well and what to improve.

Note: Your feedback form isn’t going to be very anonymous if there’s only two interviewers. This works better is there’s > 5 interviewers or so.

To be fair, most of time, student just write “it was helpful, thanks for doing this!”. Occasionally though, someone will write something more specific and that’s very helpful. For example:

When I would do interview prep with friends (and even sometimes with interviewers), they would often butt in and say “are you really sure about that?” as I was writing the solution/before I had fully explained my thought to guide me away from it. It was really helpful that discussion of the problem took place during the thinking-through stage, or when I was done one iteration of the solution. You also explained things in a fantastic manner. I learn best when interacting with someone on a subject, and your explanations immediately made a lot of sense to me (were targeted at my level of knowledge).

Keeping a journal

There’s value in keeping track of how your interviews went, especially if there’s more than one interviewer. This includes:

- What question did you ask?

- What kind of person did you interview (program, background, experience, etc)?

- What did they do well?

- What did they struggle with?

- What tips did you give?

This only requires 5 minutes of extra work and has a number of benefits. After a while, common patterns might emerge which might allow you to understand interviewing better, and students better. It helps you clearly keep track of your own progression as an interviewer. You’ll probably have interesting insights along the way. You’ll probably tweak your questions along the way. It’s nice to have this written down.

Here’s an example:

[PERSON NAME] [DATE]

- Asked my new question on a 60 seconds windows of a Twitter hashtag graph

- I need to split this question in two (try ignoring the 60 second window in the first part), there’s too much complexity to cram into your head at once. He figured out most of the implementation details in the beginning but I don’t like that the candidate takes 15 minutes before coding (because that means he has to remember 15 minutes worth of ideas while coding)

- I had a hard time producing feedback while he was coding. Need additional investigation to check if it’s because of the question or the interviewee’s performance

- Was quite methodical, figured out the problem before going into code, made up some examples to make sure his idea worked

- Has some right ideas for optimizations but I think it hit the limit of how far he could think ahead

- When you have a situation where the runtime depends on two variables that are not independent, talking about the big O runtime becomes kind of hard and not insightful. It’s better to just talk about particular extreme cases

After all, it’s because I wrote so much stuff down that I can make an interview tips video that I’m confident covers useful material, and that I’m able to write these two blog posts today!

Conclusion

I hope this blog post inspires you to go out there and offer some interview prep! Feel free to ask me any questions and if you learn anything useful, please let me know, I’d love to hear your insights!

Thanks to everyone who has volunteered for these so far, including Alex Fung, Alex Wice, Alexander Fung, Alice Zhou, Andy Baek, Bai Li, Bryan Qiu, Charles Lin, Christopher Luc, Eric Bai, Irfan Sharif, James Andreou, Joshua Hill, Keegan Parker, Kyle Lexmond, Li Xuanji, Lynn Tran, Michael Tu, Michael Young, Nima Vaziri, Robert Lin, Ron Meng, Shahmeer Navid, Shine Wang, Simon Huang, Tasti Zakarie, Tim Pei