How to learn anything - Pen spinning, DDR, rock climbing and public speaking

This is the long overdue blog post on something I’ve been wanting to share for a long time.

I recently graduated from college and looking back, things worked out pretty well. I’ve worked at a few places and lived in a few different cities. I’ve had life experiences that have helped me grow to something closer to a real adult. And I learned new skills. Among those, I feel the most important one has been learning how to learn. Through a series of seemingly unrelated events, I’ve become aware of how to methodically break down just about any endeavor into a series of approachable steps that makes anything seem feasible. I call this metaskill “skill granularization”.

granularize (https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/granularize)

- (transitive) To make granular; to divide or resolve into granules.

I’ve really wanted to spread this idea of granularizing because it’s been so helpful to me. Not only is it useful for attaining success, but does it while making success approachable and much less stressful. But I don’t want this to be yet another motivational abstract, so I’ll tell you my story of how I came to learn what I learned, and you can decide for yourself if the circumstances can apply to you.

It starts a little wacky.

Pen Spinning (2010-2012)

Pen spinning is when I first learned how to fail. Around 2010, I came across a video on YouTube I thought was pretty cool

At the time, it was the top result on YouTube for pen spinning. And, like many other people, this got me into pen spinning. In the beginning, of course, my pen spinning did not look like that at all. The first trick I tried to learn was the “thumbaround” where, as the name suggests, the pen spins around your thumb.

I wish I had a video of how bad it looked in the beginning. I would pick up the pen, try to spin it, drop it. Repeatedly, all within 4-5 seconds. Pen spinning tricks only take a few seconds to make an attempt and get ready for the next one. That’s more than 10 failures a minute…for hours. I can’t think of any other activity where you can fail at a faster rate per unit of time. Even with a conservative estimate of practicing tricks 1-2 hours a day, I would have dropped the pen more than 30,000 times in the first month.

However, the uniquely high number of (missed) attempts you can make is what ultimately made pen spinning an interesting skill to learn. The feedback loop is incredibly fast.

After an hour of trying to do the thumbaround, I was able to spin it and catch it. Sometimes. Maybe once every tenth attempt. After a week, it was starting to get consistent. Then I kept going on YouTube to watch more tutorials to learn new tricks. Then I learned to chain tricks together into a “combo”. I got to be able to do something like this:

I actively practiced pen spinning for around two years. I did it all the time, as it became muscle memory. I even got the chance to appear on TV. (Well, pen spinning isn’t a thing in Quebec, so they found 4 random high schoolers on the Internet and made a segment out of it. But hey, I got my 5 minutes of fame!)

Pen spinning practice is a closed-loop feedback system, where you can immediately feel when your pen is slipping or rotating at the wrong angle. This is in contrast to a more open-loop system, such as throwing a ball - there’s a bigger time gap between the movement you did and the result. It was also the first time that I became noticeably good at some sort of physical activity. You might laugh at the idea that pen spinning is a physical activity, and it’s true that it doesn’t have much any conditioning involved, but that allowed me to just focus on learning a new motor skill.

As I twirled my pen in daily life, other people see it. So they frequently ask me to teach them a trick. Thus, I got to see dozens of people try to learn the thumbaround. Enough to see common patterns. For example, a considerable fraction will give up after 2-3 attempts, thinking it’s something that they can’t do, rather than something they need to fail at for another hour. Not all that much for learning a new skill.

I also noticed is that almost all humans start with natural reflexes that need to be changed to learn the thumbaround. The pen needs to be pushed with the middle finger while the thumb stays still pointed up, but almost everybody points their thumb forward as they push with the middle finger. Which leaves no thumb for the pen to spin around 1!

So I eventually started telling people to focus on that one thing first: keeping the thumb still. By focus I mean, don’t even bother trying to catch the pen. Let it fall. All as long as the thumb doesn’t move. This would become an important aspect of granularizing. To learn a complex movement (thumbaround), you need to learn parts first (pointing the thumb up). But to learn the parts, you need to temporarily ignore and fail at the whole.

Focus on one thing. That was my first time consciously granularizing.

Dance Dance Revolution (2015)

Next, I learned to alternate between technique practice and pushing yourself to the limit while playing DDR.

Fast forward a few years to summer 2015. I started a second internship at Dropbox. I’m having a good time there, the work hours are reasonable. I don’t have any homework to do. So outside of intern events, my evenings are free. I can enjoy life.

While there, I met a full-timer named Nick Wu in the game room, playing DDR (Dance Dance Revolution). Yup, that game where you buy a mat, plug it to your PlayStation, and try not to embarrass yourself stepping on arrows at the rhythm of the music. But in Nick’s case, saying that he “plays” DDR is quite the understatement. Perhaps a more honest description is that it’s like watching movement so efficient it has transcended the physical realm and has joined the heavenly realms of the Japanese video game saints.

Nick playing a level 16 song (ITG). It's as hard as it looks.

Getting there takes years of practice. Nowhere in my dreams would I have thought of playing that. However, Nick commented nonchalantly that “oh yeah, you can totally get to level 9-10 by the end of the summer”. Surely he must know what he’s talking about, I thought.

I had nothing better to do, so I made DDR my main hobby for the summer (with cardio benefits!) and hung out in the game room for 2 hours a day, 5 days a week 2, alternating turns at the machine with other Dropboxers.

DDR is relatively straightforward in that most people will get better just by playing it a lot. That being said, I wanted to make sure to improve smoothly and avoid getting stuck by practicing at the appropriate difficulty level. This might sound obvious, but I’ve seen people try levels that were way too hard. They would usually give up and, even if they persisted, wouldn’t develop good technique.

In DDR, you need to learn to move efficiently and develop good reflexes. This can only be achieved by making a habit out of the correct habits. That’s hard when you can’t keep up with the arrows on the screen. So I would alternate between playing easier songs while training different aspects of DDR, and pushing my limits at harder levels. There, once I felt comfortable, I would combine what I had learned up to that point.

In DDR, techniques to practice include using rhythm to dance (rather than looking at the screen), alternating feet, crossovers (stepping on the right arrow with the left leg or vice-versa), focusing on balance, focusing on moving as little as possible, focusing on hip movements, or focusing on stepping at the corner of arrows.

By cycling between easy and hard (and a bit of coaching from Nick), I managed to make steady progress. I could do a harder level every two weeks and could consistently clear 9s by the end of the summer.

And even managed to do a 10, just once.

It was satisfying to reach that point, and a valuable experience experience. But at that time, skill granularization was still something I was becoming aware of, a vague guiding principle in the back of my mind. Furthermore, while I feel like it was useful, I didn’t improve that much faster than other people who spent a comparable amount of time, so I didn’t make a big deal out of it.

However, DDR lead me to discover rock climbing, By then, I had used skill granularization twice to get good at something, and was conscious about using it. There, I used it to improve very quickly.

Rock Climbing (mid 2016 to now)

In climbing, I learned that granularizing really works.

I discovered climbing during DDR summer when a friend that was into it, invited me to try. Upon seeing the colored holds, the variety of climbing puzzles (“routes”) designed by humans and a progression of graded levels (V0, V1, V2, …), I immediately saw climbing as a strength-based version of DDR. Instead of being all about cardio and legwork, the emphasis shifts to the core and the upper body. (I later found out that climbing is not about strength as much I thought — but that’s not important.)

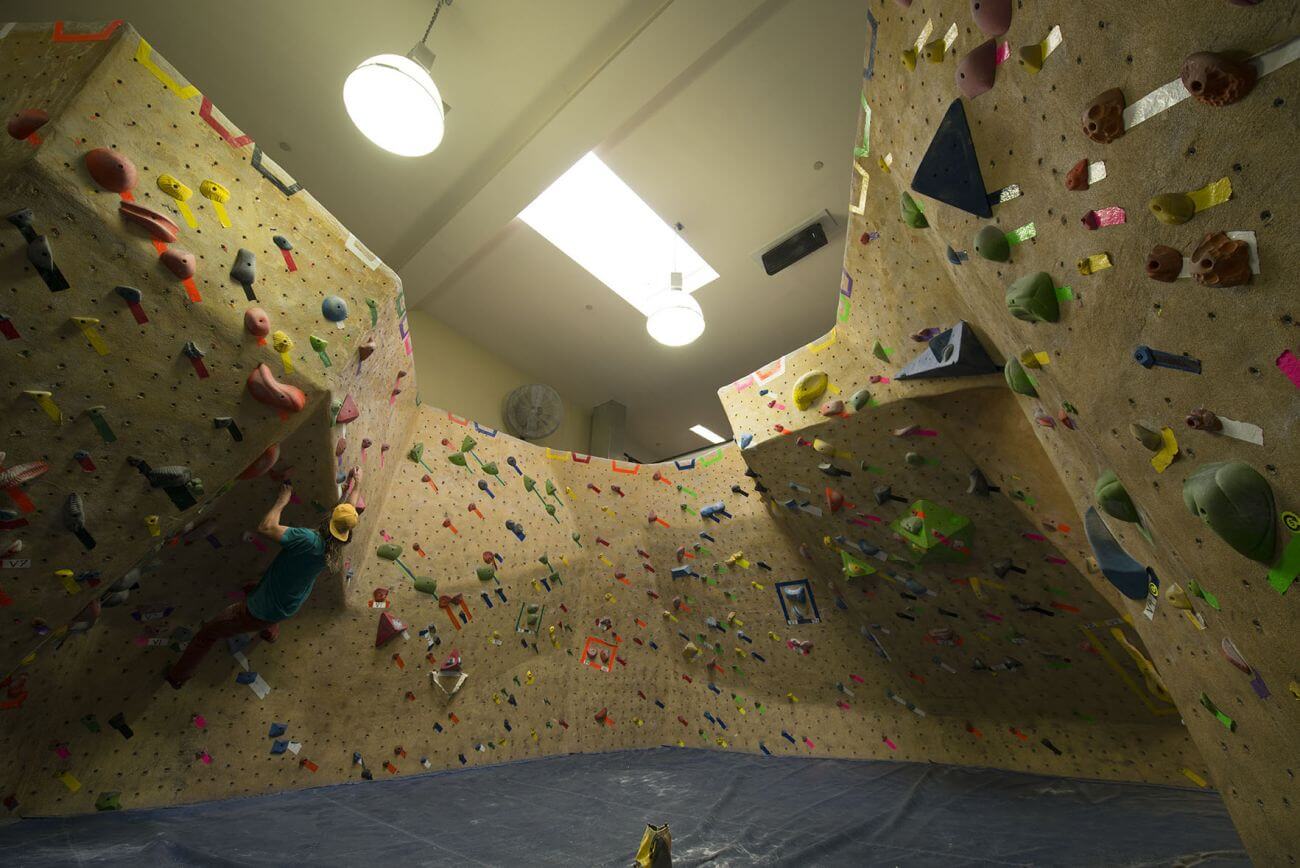

The bouldering area of Planet Granite Belmont, where I went climbing for the first time

After that first experience, I went online and watched some climbing videos that were pretty cool and inspiring. I didn’t go climbing again that summer as I wanted to focus on DDR, but made a mental note to try it next.

And I did, a year later. When I started another internship in New York in summer 2016, I no longer had free access to Dropbox’s DDR machine, but there were a lot of climbing gyms nearby. That was the perfect time to start climbing. So I planned to climb 3 times a week, and did just that.

This time, I consciously intended to use skill granularization right from the start to improve quickly. After one climbing session, I went online and looked for subskills to focus on. After one week, I went online to watch climbing tutorials. After a month, I took a quick read through “The Self-Coached Climber” to make sure I didn’t miss anything major and learned of fundamentals training drills.

What does a breakdown of climbing subskills look like at the beginner level?

- Minimize amount of work done by the arms, which are weak

- Focus on initiating movement from the legs

- Keep arms straight - bent arms tire super fast

- Twist and roll arm around body with hip twist to get lots of reach

- Reading the correct sequence to solve a problem

- Figure out how to grab the different types of holds

- Try to use holds in the direction given to you

- Attempt to find a sequence of moves that alternates the left and right hand (typical of beginner problems)

- Efficient motion

- Do the silent feet exercise to focus on accurate and stable footwork

- Use legs to move body close to the wall (especially the hips)

- Force yourself to take your time climbing and do moves correctly by doing them slowly, rather than do desperate lunges

- Understand how to flag, reverse flag and drop knee - use them whenever possible

I practiced each of these subskills a lot, on the easiest problems I could find. During the learning process, they do make climbing harder. A good example is “flagging”, the most important yet a very unintuitive technique that requires placing one foot on a seemingly random spot on the wall with no footholds. Furthermore, you have to figure out these moves in only a few seconds while hanging off a wall, while feeling your grip strength draining away.

It’s very easy to panic and default to your body’s instinctual, but inefficient ideas of how to move. That’s why these techniques need to be practiced at the easiest levels first: precisely those where you don’t need technique.

Furthermore, compared to when I was playing DDR, I had a better idea of how much granularizing helped me as I had points of comparison. I organized regular climbing outings with interns and full-timers, invited people to try, and got a few really into climbing.

Consequently, I managed to see or hear about the growth rates of a lot of people. From what I’ve observed and been told, I improved faster than just about everyone I’ve been climbing with. There are three factors to this. I was ok fit with a decent strength-to-weight ratio (I could do maybe 5-6 pull-ups). But I wasn’t the strongest. Since I was the one introducing people to climbing, I had to be the more motivated one. But I have to believe granularizing played the most significant role, especially after seeing people do inefficient movements for months that I got rid of 3 weeks in.

After 8 months, I could do half of V5 problems at Dogpatch Boulders. I currently climb at Dumbo Boulders and this is a recent climb I’ve done (probably ~V5? They don’t have labeled grades).

Around 9 months of climbing 3x a week (plus four months of climbing once a week)

So with climbing, granularizing became a habit, and I got the validation that it really works. So I got a little more ambitious.

Public Speaking (late 2016 to now)

Up to this point, I’ve used skill granularization on physical skills, like climbing. But while climbing is a difficult skill to master, it is relatively straightforward to granularize by following the advice of experienced climbers. At the end of summer 2016, I had a conversation with a charismatic senior manager at my company who brought up taking improv classes as a way to gain people skills. That gave me an idea. What if I tried to use granularization on a much bigger, broader, and harder skill to master: communication skills?

At some point in my life, my social skills were very limited and what I needed was experience meeting a lot of new people. I still do, as I have lots more to improve on. But it’s gotten to the point that the marginal benefit of talking to new people is getting lower and lower, and it’s hard to feel improvement in communication skills just from that. It’s hard to focus on only one aspect of communication in a conversation (and if you did, it’d probably look weird). Also, the feedback loop is completely open. That is, you don’t always get immediate feedback (or often any at all) on how well you did, unlike pen spinning, DDR, and climbing.

So the first step was to find targeted areas of communication that I could work on. After a bit of thinking, I came up with a list that included acting, improv, public speaking, stand up comedy, voiceover, and speech therapy. Heck, I even considered martial arts. I thought it could indirectly train presence of mind by conditioning me to highly adverse situations. I posited that if you can handle physical threats, you can handle intellectual ones too.

Then, within each of those activities, I could figure out how to break it down into further subskills.

The idea is to pick up a few activities that have concrete notions of “being good at it”. This is a lot better than hoping I will get better over time at something as vague as “communication”. Realistically, of course, each of those skills can take a lifetime to master. I’m not kidding myself in thinking I would become a different person in a few months - more realistically, I expected I’d need 2-3 years to see a significant difference.

So as a first step, I went shopping on Groupon 3 for classes. I found two that seemed interesting: a four session class at the Bay Area Acting Studio called “Intro to Acting for Non-Actors” and an online Voiceover for Beginners class.

Then, when I went back to school in January 2017, I enrolled in a full-length “Introduction to Performance” class (DRAMA 102) and a “Public Speaking” class (SPCOM 223). On the side, I also got some training on accent reduction and talking in more dynamic ways by having some conscious control on elements of speech like word emphasis, pauses, pace and pitch.

This is just the start of my experiment: granularizing communication. I’ve only been doing it for 4 months and it’s always hard to tell how much you’ve improved when the feedback loop is open. That being said, there are two things I’m sure that I got out of this: confidence and increased awareness.

Confidence is helpful in taking action to keep training. The culmination of all that training was applying to be the valedictorian, which as I wrote previously, was highly enlightening. Nowadays, while at Recurse Center, I take opportunities to present whenever possible. Increased awareness of how I can improve is also necessary to make the most out of every experience, to have one little area to focus on. This again boils down to granularization. Putting the two together allows for growth.

Maybe in a few more years, I’ll write another blog post about how this experiment has gone. In the meantime, this is what I’ve learned so far.

Takeaways

What I’ve learned from engaging in these four different activities is that a lot of learning goals can be made approachable using the following strategy:

- Break down a skill into subskills by talking to experts and reading tutorials and tips on the Internet.

- Keep breaking down subskills into smaller subskills until you can find an individual unit that you can focus on exclusively.

- Apply deliberate practice to that individual unit

- Do not worry about looking silly or failing at other units. For example, when learning the thumbaround, allow for the pen to fall until the thumb stays straight.

- While doing so, practice at a lower difficulty level than what you’re capable of doing, since learning a new thing will always feel unnatural at first.

- Once you’ve gotten comfortable with the subskill and it has become automatic, move onto the next subskill.

- Put subskills back into larger and larger skills and only then, push your limits.

I really want to emphasize that skill granularization is not an intense training regiment meant to get you to the top levels of a field. It’s a practical way to overcome the biggest obstacle that prevents people from learning a skill at all: fear that they can’t do it. I began with the silly parlor trick of pen spinning. But that was a start of a learning journey that allowed me turn turn this

into this

Which looks more intimidating? I believe most skills should be granularizable to a point where the first step is just knee-high. When the next step always looks approachable, I stop hoping for something like this

This elevator is a metaphor for a secret technique, natural talent, or something along those lines. Something that never comes. Skill granularization makes it possible to constantly feel progress without any of these. This is important. Success generates confidence. Confidence leads to action. Action leads to success. This is how I learned how to learn.

If anything, I might have been lucky to have been genetically ungifted for pen spinning. My pinky finger is bent and a whole phalanx shorter than most people’s, making a lot of tricks extremely difficult (or physically impossible). My thumb doesn’t bend backwards at all and I have no notable finger independence. So I could never attribute any success to talent. I don’t have major handicaps in DDR or climbing, but few people now know of the time where I was the shortest, skinniest kid that would always get picked last in gym class.

Finally, as I hope my story can convey, it can happen very indirectly. I mean, I started with pen spinning of all things. It doesn’t get sillier than that. Which is why I’m not suggesting that after reading this, you should rush out to apply skill granularization to a big challenge in your life, whether it be social skills, math, dating, sports, painting, or whatever. I’m merely suggesting to be aware of how you can improve at the subskills of whatever you decide to do next.

In the end, any skill is learned through practice and repetition. So it only makes sense that, to learn the skill of learning effectively, you need to practice learning many different things.

However small and insignificant they may be.

Further readings

The Art of Learning

Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise

Thanks to Allan Mukundi, Hang Lu Su, Indradhanush Gupta, Jamie Brandon, Julia Evans, Laura Lindzey, Logan Buckley, SengMing Tan, Shirley Du, Veit Heller, and Wesley Aptekar-Cassels for reading over and reviewing this blog post, helping cut the cruft and keeping it focused!

-

I even made a slow motion tutorial to emphasize that point. ↩

-

It was mostly for fun, DDR was rather addictive. To be fair, playing for 2 hours almost every evening is quite a lot even looking at it now. A friend commented that I can have an abnormal amount of discipline sometimes. ↩

-

It turns out Groupon is a good way to find classes for a variety of skills. I also like to use it to find activities to do in a new city. ↩