How hard is music analysis? Five type of musical events

The post is the first of a few on my current CS interest, music analysis. Let's walk through how we would think about analyzing an MP3 file. This is not a very technical post, so non-CS folks, don't run away just yet~

The average citizen understands basic musical concepts: a song is made of notes, notes have various duration and pitches, and by varying duration and pitch, we get melody. In fact, even without formalized musical concepts, plenty of evidence from tribal cultures show that the brain appears to have an innate understanding of music and rhythm.

Now, how do we get a computer to understand the same concepts?

First of all, what is sound? Physically, what we perceive as sound is vibrating air molecules that hit the eardrum at particular intensities and frequencies.

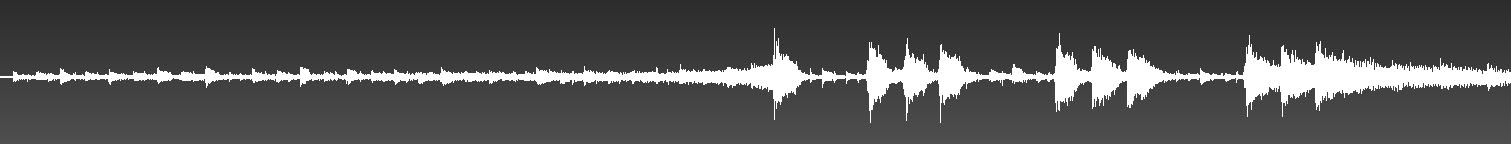

Above shows the opening of Eye of The Tiger. This is called a waveform - it represents the vibration that your speakers will produce, how the intensity of a sound varies with time. The guitar notes in the beginning are distinguishable as tiny peaks and on the right, we see the set of three accented notes iconic to the 80's song as large peaks. So far so good. We need to look at peaks.

What about a segment of Star Wars?

Well the waveform certainly doesn't seem to give us much useful information. Peak detection is not going to do much here. Furthermore, volume is certainly not the only thing that matters in music - pitch does too right?

Pitch, as we perceive it, is just a measure of the frequency at which air molecules oscillate back and forth. Deep bass will reach lower frequencies, a trumpet will reach higher frequencies. Now what also oscillates back and forth? Sine waves!

Sine waves have different amplitudes and frequencies. Sounds like volume and pitch? Indeed. Using the magic of mathematics, Fourier showed in the early 19th century that it was possible to approximate any function with a sum of sines and coses of various amplitudes and frequencies. In fact, if you add up enough of them (infinitely many), it is possible to represent any function - including discontinuous functions and nowhere differentiable fractal curves - as a sum of periodic sines and coses. That includes sound! It is quite outlandish if you think about it. Those are called fourier series and it is possible to convert functions back and forth between their time domain representation (the familiar one) and their frequency domain representation: i.e., information about the amplitude and frequencies of the sine waves that make up the function. A nice technique to do that is the Fourier Transform and the algorithm that does it, making your iPod work, is the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT).

I'm sure many readers already know this, but I probably lost some other in that last paragraph. And that's part of my point. While the problem of representing a time domain function in its frequency domain is a solved problem, the process is complicated. The human brain is pretty darn good to be able to do something similar. Of course, it's also a matter of having different type of sensors in the ear that responds to different frequencies, but nonetheless.

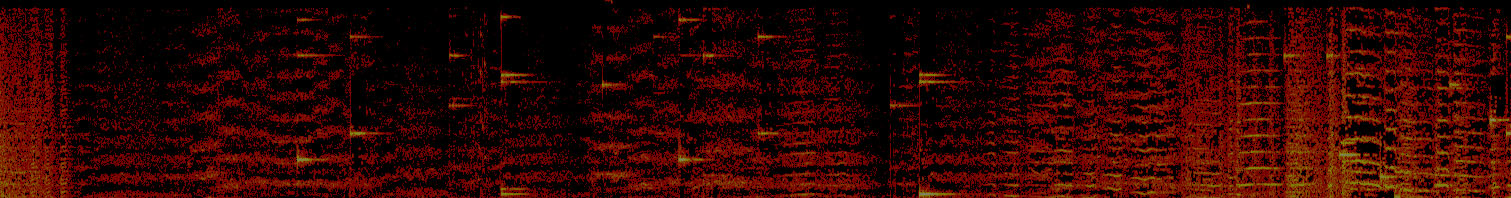

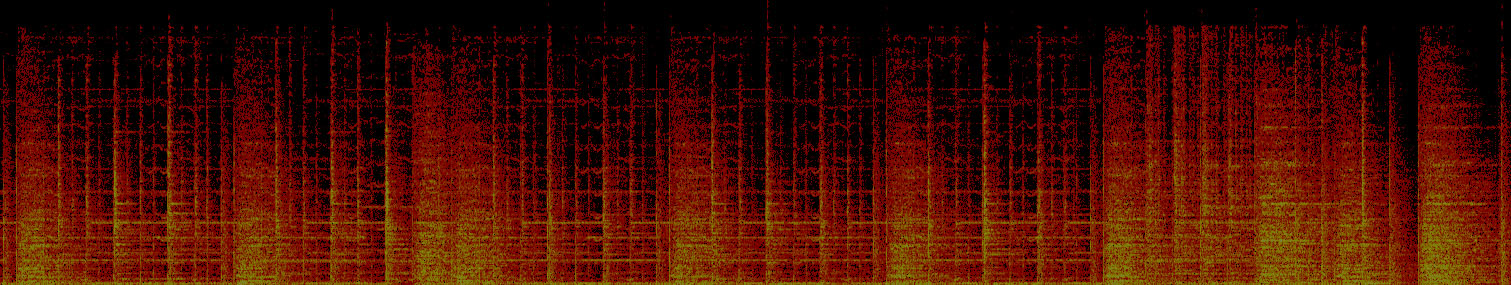

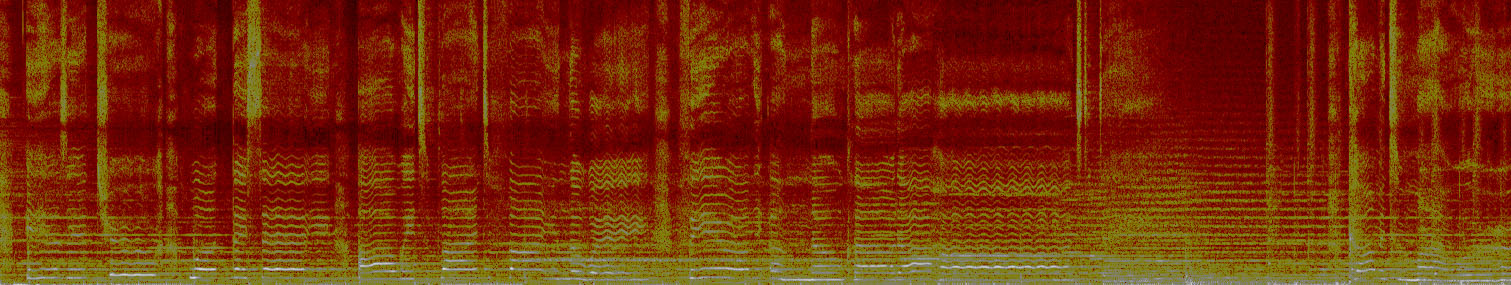

Applying a variant of the FFT, the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), which is essentially just doing FFTs on 43ms intervals of the song at the time, we'd get this, for the above Star Wars segment.

The graph shows low intensity sounds on the bottom and high intensity sounds on the top, with color indicating intensity. Notice those bright spots in the middle. They correspond to the twinkles in the song. The technical term used in the field of audio analysis for such events are onsets - a point in time where volume increases considerably. They correspond notes, naturally. The STFT works! This graph is called a spectrum.

Five types of musical events

Now, everything I've written so far is basic signal processing theory. I could have taken the lazy route and copied it from a textbook if I wished, which I implemented in a program as a basic exercise. Now that we've got the base, what next?

Let's see what is involved if we want to detect notes. Just notes; not pitch, not beat, certainly not instruments or god forbid, lyrics. Just notes.

1. Onsets

Well we've seen onsets.

They can be described as an increase of volume at a particular frequency; our typical idea of a musical note. Piano songs have easily identifiable onsets.

There are many ways this could be detected, such as finding local maxima or some form of pattern detection. It is not a hard problem.

2. Vertical Onsets

What happens with percussion instruments?

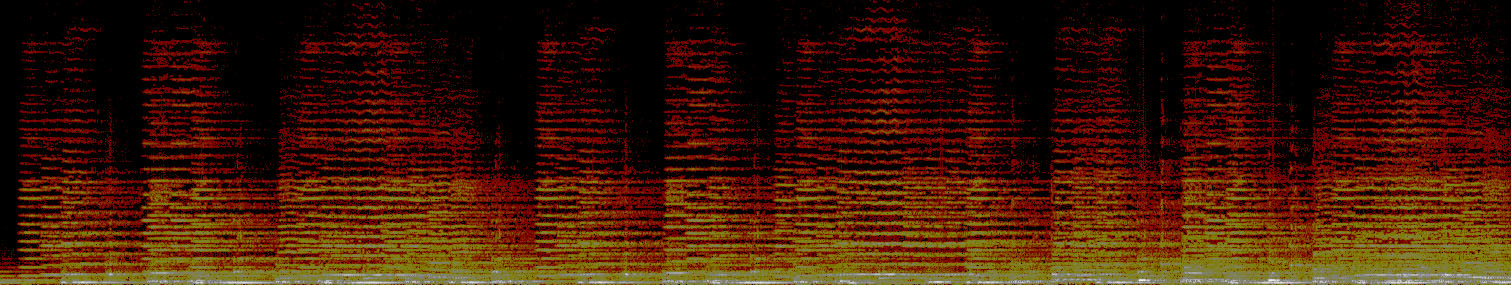

Here the onsets are clearly not localized at any given frequency. On the other hand, they still represent sharp increases in volume. In fact, it allows them to be easier to see, for our eyes, if nothing else. Since that is the case, perhaps we can use some techniques from the field of computer vision - such as edge detection.

Applying a one-directional gradient (derivative) on the spectrum and elimination non-maxima points appears to give useful information. At this point, we can just look for strong vertical lines. Many instruments, including non-percussive ones and usually the bulkier ones, will produce a similar spectrum.

3. Horizontal Onsets

When it comes to piano and drums, the moment we hit a note, a loud sound is produced. It is explosive. On the other hand, certain type of instruments, such as strings, are generally used differently. The raise in volume corresponding to a note is more progressive and spread over a period of time. Furthermore, the note can be held at constant volume for a long duration. Such an event can still be picked up by looking at the gradient, but the signal will be weaker. It will be more difficult to distinguish from noise and, if mixed with other instruments, may have its signal buried, even with some relative threshold.

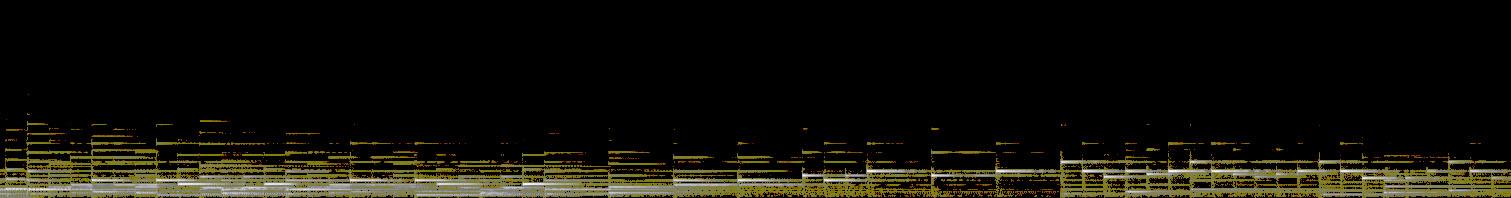

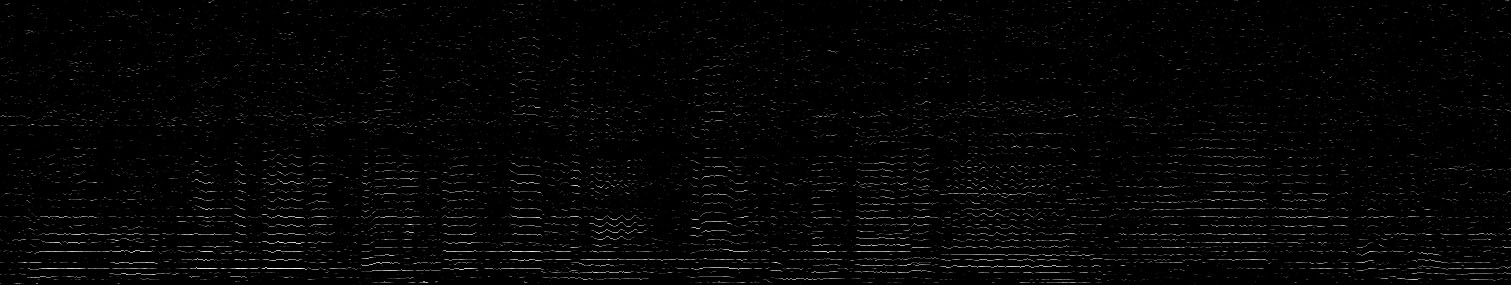

This is a snippet of a string-only song, to illustrate my point. Taking the one-directional gradient, the onsets are still stronger than noise (brighter points in the graph), but setting a proper threshold is very error-prone.

On the other hand, rather vertical lines, we see horizontal stripes. Discontinuities along these stripes correspond to a new note which, more often than not, has a different pitch than the previous note and thus, is located at a higher or lower frequency. Taking the gradient in the other direction detects such signals quite nicely.

Each note appear in multiple frequency bands - in fact, it appears throughout the entire frequency spectrum! It's not completely unexpected that such a thing would happen. Chords, by definition, is a set of different notes at different pitches played simultaneously. However, there shouldn't be as many as 10 different notes in the same chord in a simple sound. Many of the horizontal stripes we detect are artifacts of the fast fourier transform, a repetition of the original note. They appear because we are working with discrete and non-periodic signal rather than real functions.

The phenomenon is called spectral leakage. As far as note detection is concerned, they could be an issue if it causes multiple different instruments in different frequency bands to begin overlapping and masking each other. In general though, it could also give a margin of error in case the original signal is not detected. The algorithm becomes more complicated, but the accuracy is likely to remain unaffected (these are all conjectures by the way - I have yet to test such claims).

Of course, if the goal was to detect pitch, the process would certainly become more difficult.

4. Footprints

Detecting horizontal onsets is simply a matter of iterating through a set of pixel on the time axis at a fixed frequency. Detecting straight lines in general is a harder problem, but are achievable with algorithms such as the Hough transform.

Undulating lines are much more challenging. Some could already be seen in the To Realize's spectrum. Instruments such a violin often involve alternating between two pitches continuously and the human voice and easily switch from one pitch to another continuously. The resulting patterns are reminiscent of footprints left on the snow, hence the name.

See Who I Am - Within Temptation

Footprints may or may not need to be handled as a special case, but an algorithm that ignores their existence may fail to detect these entirely, or associate a separate event to every undulation.

Just like every shoe as a different pattern, different singers and different lyrics will leave different types of footprints. For someone interested in analyzing lyrics this would be a difficult problem to tackle.

5. Clusters

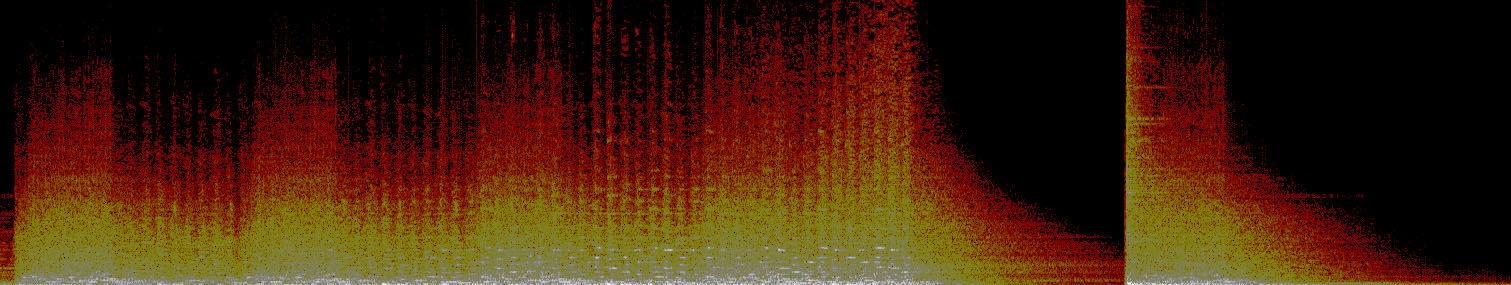

Although I'm sure there's more, one last type of musical event I will talk about are clusters. These are typically loud sound effects, not necessarily instrumental, played in isolation. I'm sure many of you have heard this one before :

Similarly with strings, where does the note start? The volume increases progressively, so vertical edge detection does not work very well. Horizontal edge detection will not achieve much either as there are no horizontal stripes.

However, it would certainly be feasible to construct a measure of energy (as some researchers have done) to detect such clusters. The only problems is that since clusters are large, they require iteration and summation through large quantities of pixels, which needs to be carefully optimized to get a reasonable speed.

Conclusion

When it comes to music analysis, even note detection requires the capacity to handle many different kind of events. Pitch detection and feature detection would require even more clever techniques. On the other hand, the difficulty of this task only serve to make the problem more interesting. I will post further updates if I come across interesting discoveries in my research.

Note : While I'm sure someone has published a paper classifying different type of music events in a spectrum, I have not found one while going through music analysis literature yet. The terms I use (except for onset) are not, in any way, technical or official.